Politicians, civil servants and people in Cape Town's property industry are at a crossroads. The next few months will tell who is committed to building an inclusive and spatially just city.

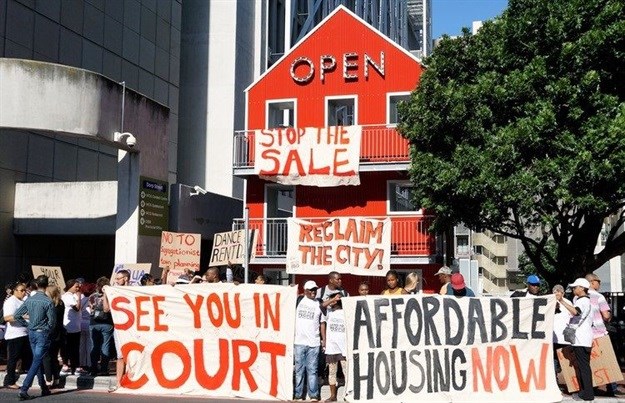

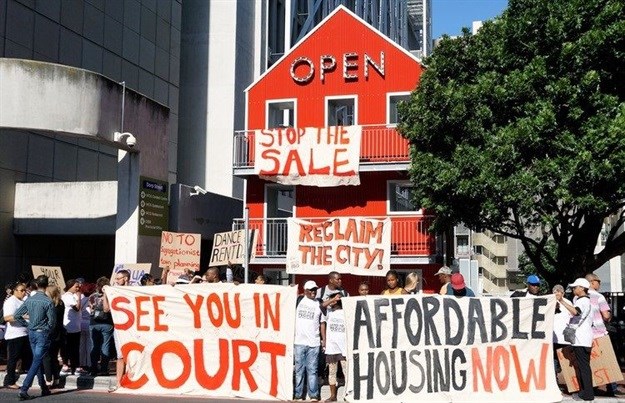

Reclaim the City supporters protest in April 2016. Archive photo: Naib Mian

A black majority live on the densely populated urban periphery, in townships, as backyarders or in informal settlements, while the wealthy continue to live in low density mostly white suburbs in well-located areas.

Over the last year, Ndifuna Ukwazi has been objecting to exclusive and unaffordable private developments across the city of Cape Town. Our concern, shared by many, is that this pattern of spatial planning has negative long-term fiscal, social, environmental and political costs and is ultimately detrimental to the sustainability of the Western Cape economy. In effect, this pattern replicates the apartheid city.

For example, to buy an average one-bedroom apartment selling for R1,250,000, a household would have to pay at least R12,270 per month in bond repayments. To pay this, a household would need to earn a minimum monthly income of at least R36,800, assuming that the bond repayment is no more than one third of income on a bond.

Most poor and working class families are between three and five people in the household, so even if the family can afford to buy a one-bedroom property, they may not be able to fit. So to measure access, we need to be able to determine how many household can both afford and fit. Our estimate is that a maximum of four people could fit into a one-bedroom home comfortably.

Extraordinary exclusion of the majority of resident

Based on 2011 Census data, only 118,133 of all households living in the city, or 11% could both afford and fit into a one-bedroom property. If we break the number of households down by race, the results are staggering: Black African households who can both afford and fit represent only 1% of all households in the city; likewise Coloured households represent 2.2%; Indian households represent 0.3%; and White households represent 7.3%. It demonstrates the extraordinary exclusion of the majority of residents from the housing market, which is most acutely felt by black (Black Arican, Coloured and Indian) households.

The basis for Ndifuna Ukwazi’s objections is the Spatial Planning Land Use Management Act of 2013 (SPLUMA), which establishes a set of compulsory principles applicable in every land use decision. These principles are spatial justice, spatial sustainability, and spatial efficiency.

The principle of spatial justice, in particular, is consistent with the Constitution’s transformative aspirations. It aims to address spatial imbalances by improving access to land. Land use decisions must address the colonial and apartheid era dispossession and exclusion of black people, and provide new opportunities today.

To date, the City of Cape Town has not implemented their statutory obligations. This means a core legislative principle that should be at the heart of all planning approvals has not been realised practically in land use management on individual applications.

Empowered to redress spatial imbalances

Both the city and the Municipal Planning Tribunal (MPT) are mandated to redress spatial imbalances and empowered to impose conditions that mitigate against exclusionary developments. One way to do this would be for the city to ask for a fair and proportional contribution from developers towards affordable housing. To date, both city planners and the MPT have refused to do this, arguing mainly that there is a lack of policy guidelines.

Internationally, cities have passed inclusionary housing policies to secure a fair and proportionate contribution towards affordable housing on-site (in the development), off-site (on well-located state owned land), or as a fee in lieu in exchange for the value unlocked through the granting of land use rights.

To address this, mayoral committee member for transport and urban development (TDA) Brett Herron has committed to bringing a policy to council as a matter of urgency. Last week, the city’s mayoral committee approved a concept document on inclusionary housing, which now opens the way for engagement.

While the TDA is in the process of drafting policy, it is not certain. Some politicians and officials seem adamant to shut down the inclusive agenda that the TDA has embarked on in the belief that a policy would be damaging to the property and development industry. This would be a mistake.

Responsive inclusionary housing policy

A good inclusionary housing policy would, in fact, stimulate density and new development in well-located areas and along transport corridors. This could be done by creating a density overlay zone in the current bylaw, which would grant additional rights as an incentive in exchange for affordable housing. Developers would be able to build higher and denser as long as this is more inclusive.

This would only work if the inclusionary housing policy was responsive to the ebbs and flows of the property market and across different areas. A blanket percentage would not work. So, for example, in areas where the value of land is high and the market is hot, the contribution would be higher. In areas which are well-located but have less hot markets, the city could increase the incentive but reduce the contribution.

An inclusionary housing policy should not be punitive, and the contribution could be paid for through any additional profits, efficiencies in the planning application system, and the ability to negotiate down land costs.

An effective inclusionary housing policy would dovetail with and help to unlock the city’s significant stock of smaller parcels of land for social housing that it is unable to develop itself due to the small economies of scale. Inclusionary housing, could be the very mechanism that is needed to advance inclusive transport-orientated development.

It is clear that a change in the bylaw and a policy is needed urgently to create certainty and manage the significant risks that must be navigated in the current economic environment. Further delays from the mayoral committee and within council present the greatest risk to the industry.

Policy not required

Policy would be preferable but it is not required for the city and MPT to impose conditions to secure affordable housing.

It is up to developers to justify how their development complies with principles of spatial justice, and why a condition for affordable housing should not be imposed.

In a ruling on an appeal to the development application for Zero2One skyscraper, Mayor Patricia De Lille, after seeking the opinion of senior counsel, confirmed that the city and the MPT can impose conditions for the contribution of affordable housing in private developments without having a city policy in place.

According to the mayor’s ruling, a condition for a fair and proportionate contribution towards affordable housing in a private development can be imposed if three requirements from section 100 of the City of Cape Town’s current Municipal Planning Bylaw are met, namely, the condition must be:

1. objective;

2. reasonable; and

3. “arise from the proposed use of the land”.

If it is undisputed that a development is spatially unjust, and the city and MPT has the power to fix the problem, neither the developer nor the city or MPT can ignore the problem. Approving a spatially unjust application with no reasonable justification or attempts to fix the problem is unlawful. This opens up the decision to be reviewed in the courts.

Choice for developers

Depending on how you view the situation, this poses a choice for developers: Wait for policy to be passed, which will provide more clarity for what is expected from developers; or preempt policy and possible delays by submitting applications which include a fair and proportionate contribution of affordable housing now.

There are four good criteria to think about when considering whether a housing project in the private sector advances spatial justice. It must promote equal opportunity to black households, be truly affordable based on income, be well-located and use the right mechanism to ensure it is retained in perpetuity (which means it stays affordable in the long term).

There is now an opportunity for developers to make sure that an inclusionary housing policy works for them not against them, to explore ways to build affordable housing feasibly, and to contribute towards an inclusive, efficient and sustainable property developments that bring both economic and social returns for the industry and our city for generations to come.

Article originally published on GroundUp.