Subscribe & Follow

Trending

Vicinity Media: How we use DOOH in our retail solutionSharné Daniels, Chanté Naidoo & Olav Westphal

Vicinity Media: How we use DOOH in our retail solutionSharné Daniels, Chanté Naidoo & Olav Westphal

Court rules that banks can sell your house for next to nothing

This has raised the question of whether the bank should be allowed to sell the debtor’s home for an amount that is at least equivalent to the outstanding debt or to sell the property at any price.

This was the subject of a Pretoria High Court judgment handed down on 22 March 2018. The court dismissed a challenge against the constitutionality of certain rules of court which enable the home of a debtor to be sold without a reserve price.

Background

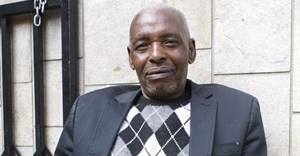

Given Nkwane obtained a home loan from Standard Bank in September 2011 for an amount of R380,000 and had a mortgage bond registered in favour of the bank. Nkwane defaulted on his home loan in February 2012. For the rest of that year he continued to default and only managed to make some of his payments intermittently.

In January 2013, he applied for debt review, but this was unsuccessful. In March 2013, he applied for rehabilitation (this would enable him to pay substantially less for his monthly instalment). This application was approved by the bank.

However, by July 2014, Nkwane informed the bank that he could no longer afford the instalments and wanted to sell his property. The bank informed him that he must use the bank’s Easy Sell mandate to do this (this is Standard Bank’s programme to help distressed home owners sell their properties). Nkwane was unable to do this, however, because his wife refused to sign the Easy Sell mandate.

The bank then instituted legal proceedings against Nkwane and successfully obtained a warrant of execution against Nkwane’s home. A warrant of execution enables a creditor, such as a bank, to attach a person’s property and sell it.

At the sale of execution, the house was sold for R40,000. At the time of the sale the insurable value of the house was nearly R500,000.

Court proceedings

The primary issue the court had to determine was the constitutionality of rule 46(12) of the High Court rules which enable a creditor to attach and sell a debtor’s home without a reserve price being set. Under this rule, it is possible for the bank to sell a debtor’s home for any price and recover any amount they can for the outstanding debt.

After proceedings had already begun, the rules which were the subject of the dispute were amended in December 2017. In terms of the amended rules, a court can set a reserve price in certain circumstances but has to consider at least nine factors before making such a determination.

Before considering the constitutionality of the rule in question, the court considered two other related High Court judgments which had been handed down after proceedings had begun. These two judgments had upheld the constitutionality of the rules. In its reasoning, the court placed much reliance on these two judgments and effectively reached similar conclusions.

In reaching its decision, the court considered four main issues, explained below.

Will a reserve price result in a home being sold for a higher price?

Nkwane argued that setting a reserve price will ensure that a debtor’s home is always sold for a higher price. The court however found that this contention was unsubstantiated. Instead, the court found that the bank had provided ample evidence as to why a reserve price would not result in a higher price being obtained.

These reasons included: a sale in execution is a forced sale and consequently results in lower prices being obtained; the conditions of a forced sale often render the buyer liable for outstanding rates and taxes; and a buyer may be faced with long and drawn out eviction proceedings to remove any occupants from the property. The bank also pointed out that a reserve price will reduce interest in the sale and may result in the property not being sold at all. This would inevitably prejudice both the debtor and creditor. The court accepted the bank’s submissions.

Does a sale without a reserve price constitute an arbitrary deprivation of property?

In terms of the Constitution, everyone has the right to not have their property deprived of them arbitrarily. Nkwane argued that the sale without a reserve price affects a debtor’s right to equity in the property because the property is not sold for its real value but a forced value. Nkwane also argued that because the sale may not even result in the recovery of the full outstanding debt (as in Nkwane’s case) the sale without a reserve price is arbitrary and serves no legitimate purpose.

But the court found that to the extent that the sale does result in a deprivation of property it could not be regarded as arbitrary. This was because the rules enabled a relatively cheap and expeditious process for the bank to recover some of the outstanding debt. Furthermore, the court relied on previous High Court decisions that maintained that there are compelling socio-economic reasons for the existence of mortgage bonds and the existing debt recovery process.

Lastly, the court found that in any event the deprivation of property did not flow from the sale per se but rather from the failure to pay the outstanding debt.

Does the fact that the rules were subsequently amended mean that the previous rules were defective?

The court considered the fact that the amended version of the rules enables more judicial oversight over the process and allows a reserve price to be set in certain circumstances. However, the court found that while the amended version of the rules may well be an improvement, they did not render the previous version of the rules irrational or unconstitutional.

Does the rule infringe upon the right to adequate housing?

Nkwane contended that the rule did so because it may result in a debtor being blacklisted which would prevent them from accessing the housing market in future. Secondly, Nkwane contended that it could never be considered fair, balanced or justifiable to sell a house valued at R470,000 for R40,000 to realise a debt of R370,000.

The court found that any resultant blacklisting is not as a result of the sale in execution but rather the debtor’s failure to pay the outstanding debt. The court also found that because there is judicial oversight over the process of determining whether a house is specifically executable before a warrant of execution is issued, the right to adequate housing is already protected. As such, there was no need for further protection in the form of a reserve price.

Lastly, the court found that the question of whether a reserve price should be set or not is in fact a policy decision which is best left to Parliament to determine. For this reason, the court rejected the submissions of the South African Human Rights Commission who had been admitted as a friend of the court. The SAHRC had highlighted the fact that several jurisdictions including Ghana, Germany and South Korea do require a reserve price as the default position.

Decision will be appealed

The judgment has major implications for the right to access adequate housing and the financial position of debtors generally. Although the amended version of the rules, which came into effect in December 2017, enable a reserve price to be set in certain circumstances this is still not the default position.

Debtors whose homes were attached prior to the amended rules will still be in a potentially precarious position. For this reason, Nkwane’s lawyers, Lawyers for Human Rights, intend to appeal this judgment. It remains to be seen whether a higher court will reach a different decision.

Source: GroundUp

GroundUp is a community news organisation that focuses on social justice stories in vulnerable communities. We want our stories to make a difference.

Go to: http://www.groundup.org.za/